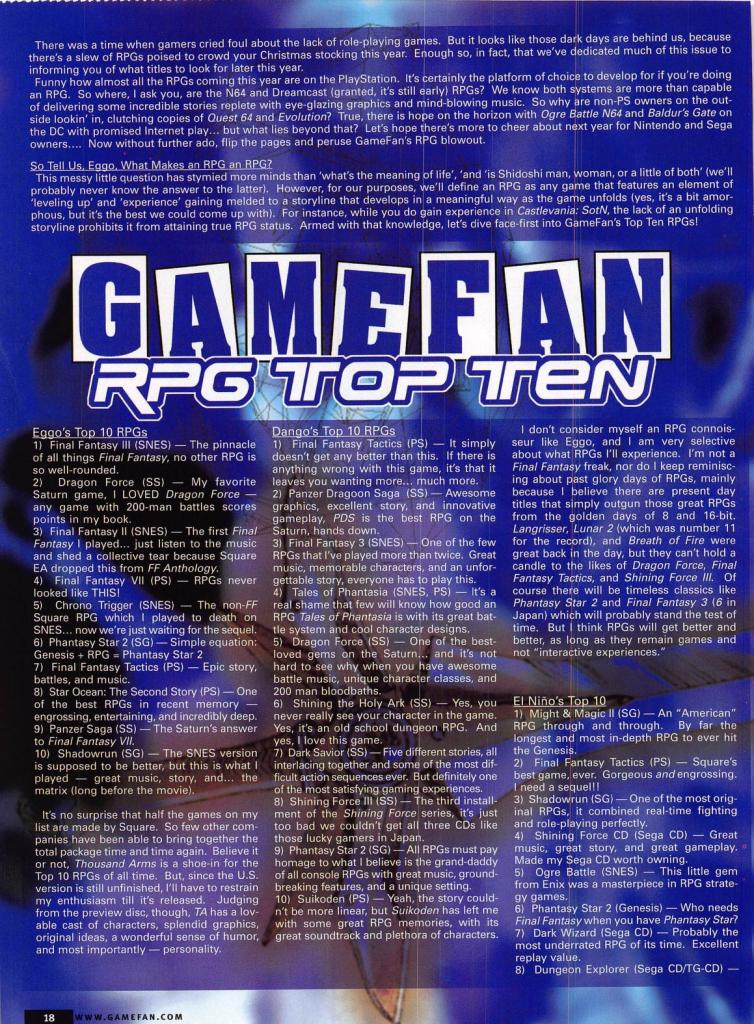

The critical and commercial success of Final Fantasy VII (Squaresoft, 1997) signaled that Japanese role-playing games (JRPG) were both a product and genre viable enough for global consumption despite earlier JRPGs already experiencing a modicum of success abroad. Yet, whatever great promise Final Fantasy VII would bring to the genre was largely limited to the Final Fantasy franchise with even other games in Squaresoft’s catalogue being ridiculed for being too strange, thus, IGN calling SaGa Frontier (1997) “shite.”1 Likewise, recall the August 1999 issue of GameFan magazine in which the editorial staff gathered to discuss their top 10 RPGs of the decade. It’s no surprise to see Final Fantasy titles dominate the lists, but one particular critic, Geoffrey “El Niño” Higgins vehemently disagreed with his colleagues, writing: “That’s right, no Final Fantasy series…The obsession with Japanese RPGs baffles me, considering how much better U.S. titles are (Bard’s Tale, Wasteland, Might & Magic and a little license I like to call AD&D…need I go on?).”2 The turn of the new millennium was thereby marked by an increasing distaste towards Japanese games and products that were either explicit in their Japanese origins or deviant from the design structure of Final Fantasy.

With Microsoft entering the console market, such feelings would only worsen as they introduced PC Western RPGs such as The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (Bethesda Game Studios, 2002), Jade Empire (BioWare, 2005), and Mass Effect (Bioware, 2007) to a wider audience who wondered why Japanese games were linear and melodramatic, elements that were seen as rendering the genre as embarrassing—one need only look up archival reviews of X-Play to see the show switch between begrudging praise and xenophobic humor. Coupled with the arrival of high-definition (HD) and the ensuing desire for realism, JRPGs which were either still using retro or anime style graphics were derided. Furthermore, the ever stalwart Square Enix would begin to falter. While Final Fantasy XI (2002) and Final Fantasy XII (2006) did well enough, the box-office failure of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (Hironobu Sakaguchi, 2001) and the departure of Hironobu Sakaguchi and later, Yasumi Matsuno, left a pallor over the company, and the direction of the franchise.

Japanese developers would begin to take note of Western tastes, culminating in the Final Fantasy XIII trilogy looking towards the likes of The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (Bethesda Game Studios, 2006), Mass Effect, and Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (Infinity Ward, 2007).3 For Western gamers, Final Fantasy XIII (Square Enix, 2009) would bear the burden of saving the entire genre. Take the headline of one article from the U.K. gaming magazine 360, “Could Final Fantasy XIII: finally transform the JRPG?”4 According to reviewers, who especially lambasted the game for being too linear, Final Fantasy XIII neither saved nor transformed the JRPG.

However, since then, JRPGs have exponentially grown in popularity with titles of formerly niche franchises like Persona 5 (Atlus, 2016), Nier: Automata (Platinum Games, 2017), and Yakuza: Like a Dragon (Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio, 2020) firmly entering the gaming mainstream as a result of strong sales. But if the anxieties surrounding the success of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 (Sandfall Interactive, 2025) proves anything, it’s that the negative perception surrounding Japanese games has never gone away.

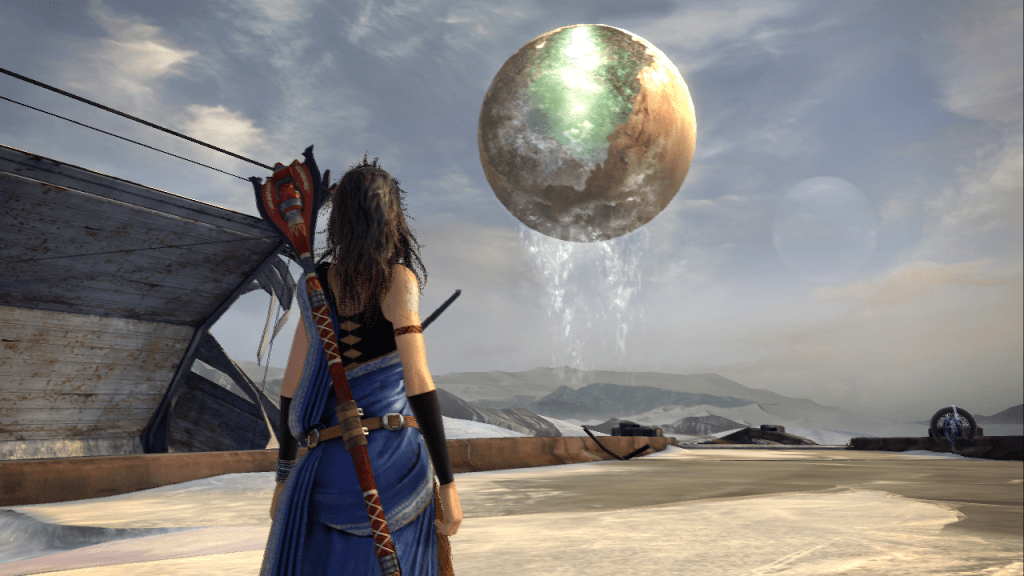

Earlier at this year’s Game Awards, Clair Obscur swept the ceremony, winning nine awards in total, including Game of the Year. The game has been successful enough for Sandfall Interactive to have received congratulations from the President of France, Emmanuel Macron, with Macron commenting in an Instagram post, “…et oui, c’est Français!” (“….and yes, it’s French!”), a choice of words that at once claims Clair Obscur as an explicit cultural product of France. One can imagine that in the same manner which Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk gifted U.S. President Barack Obama a copy of The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings (CD Projekt Red, 2011), Macron will gift future dignitaries a copy of Clair Obscur as a representation of French culture. Certainly, the game is French to the point of parody, an element that Sandfall have purposefully played up through the inclusion of French cultural stereotypes, including baguettes, mimes, and berets. In this manner, Clair Obscur recalls the Tengai Makyō series which similarly draws upon Orientalist notions of Japan and the Far East, going as far as claiming the games themselves are based off the work of P.H. Chada, a fictional scholar of East Asia. Yet, while Clair Obscur has become canonized within French culture, Sandfall themselves have also been explicit in their reverence for the Japanese games which inspired them, with several members of the development team citing titles such as Final Fantasy VIII (Squaresoft, 1999), Persona 3 (Atlus, 2004), and Elden Ring (From Software, 2022) as influences, and the game’s director Guillaume Broche thanking Hironobu Sakaguchi during his acceptance speech for Game of the Year.

But the intent behind Sandfall’s words matter little when Clair Obscur has already been alchemized into a remedy for the supposedly failing JRPG genre. Being French matters in so far that it seems to serve as proof that Japanese developers themselves have become stagnant. Clair Obscur thereby borrows the grammar of the JRPG without the associated baggage of the product itself being Japanese. As Mia Consalvo argues, such maneuvers predate the video game industry and can be traced back to the late 19th century Japonisme movement in which Western art drew influence from Japan.5 In this regard, the game is part of a broader lineage of transnational exchange. However, the underlying anxiety is that Clair Obscur will be turned into a bludgeoning tool against Japanese developers. It is no secret that in recent years former JRPG juggernaut Square Enix has been struggling both financially, and perhaps creatively, with the developer themselves announcing that major titles such as Final Fantasy XVI (2023) and Final Fantasy VII Rebirth (2024) failed to meet profit expectations.6 It did not help then that on a recent trip to Japan, members of Sandfall met with Square Enix, sparking rumors online that Sandfall would be developing a Final Fantasy game.7 Here were the saviors of the JRPG arriving to usher in a new golden age, one that would return to the familiar designs that helped popularize the genre in the first place—turned based combat, open-world exploration, and cinematic storytelling,

Such arguments directed towards the “failing” Japanese games industry are far from new. In a 2010 interview with the New York Times, Keiji Inafune decried Japanese games as awful, claiming that the Japanese industry has fallen behind.8 Phil Fish would express similar sentiments when at GDC 2012, he told Makoto Goto, Japanese games “just suck.”9 Combatting the rise of this negative perception towards Japanese games, in 2010, the now defunct Imageepoch held a press conference titled, “JRPG sengen kekkai” (“The JRPG Declaration Rally”), where the developer announced a slate of new projects meant to revitalize the genre, including The Story of the Last Promise (2011) and Black Rock Shooter: The Game (2011).10 Yet, these titles ultimately either went unlocalized or released to lukewarm reception and were quickly forgotten by all except die-hard aficionados who recognized and appreciated Imageepoch’s experimental approach to the genre. History repeats itself as earlier this November, Katsura Hashino announced that Atlus would be developing the “JRPG 3.0.”11

So why has Expedition 33 been so successful in ways that its Japanese peers have not? Or rather, why have discussions framed it as the future of the JRPG? Is it a matter of aesthetics wherein games that explicitly look like anime—that is to say, cartoons—are not taken as serious cultural objects? In a series of Bluesky posts, media scholar turned self-help guru, Ian Bogost, decried those who still viewed games as being a unique medium for storytelling, a failed attempt to revive a debate concerning narratology and ludology. But it was while charging at windmills that Bogost suddenly sought to put down Japanese games: “Q-Up and Candy Crush, say, are more serious works of game than Horses (which seems fine and even innocuous!) or whatever embarrassing anime RPG trash is on Steam or Nintendo EShop.”12 For Bogost, the term serious can, “…imply substance, a window onto the underlying structure of a thing,”13 and while he ultimately prefers to use the term “persuasive,” it is clear that “anime RPG trash” is incapable of having such substance. It is wrong to equate the aesthetic design of anime with the entire country of Japan but following the logic of those who do reveals the heart of the matter.

In their own recent article on the discourse surrounding Clair Obscur, Harper Jay suggests that the game’s success emerges from its appeal to cinema, a medium which has now long been used as a shorthand description for artistic.14 As Jay writes, “Throughout the 2000s, video games have grappled with this fear, seeking all kinds of ways to invite praise and seeking a kind of respectability. Mostly, this means intimating films many years after they’ve done something…”15Games scholar Andrea Andiloro makes a similar argument, tracing discourse in video game magazines which posited that games could never be as serious as films—what Andiloro calls, “cinema envy.”16 Square themselves would employ marketing strategies for Final Fantasy VII that placed the game in opposition to cinema, going as far producing a theatrical commercial filled with FMV sequences and a voice-over that announces, “And now the most anticipated epic adventure of the year will never come to a theater near you!” So although Final Fantasy VII contains visual references to Japanese historical and popular culture, from Tokusatsu films like Zeiram (Keita Amemiya, 1991) to the duel between Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojirō, the game’s cinematic storytelling—to borrow Jay’s words—invited praise and respectability.

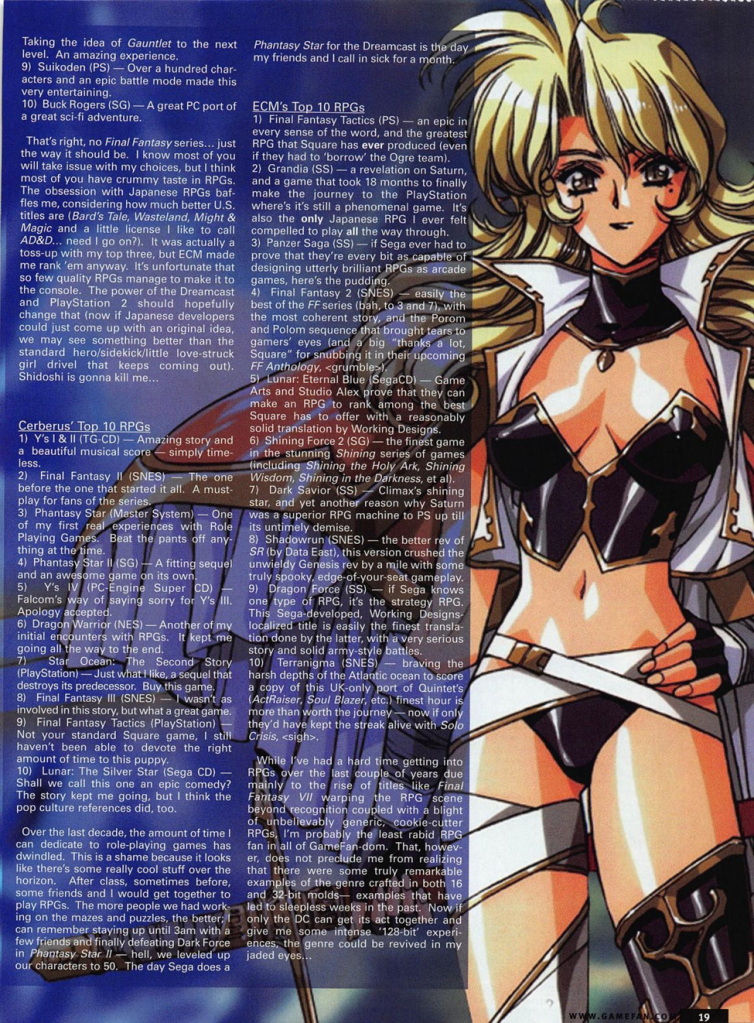

While members of Sandfall have discussed the influence of other artforms on Clair Obscur, including cinema, and the labor of staged rehearsals for mocap performances,17 the game has not been marketed as a “cinematic” experience the same way that Final Fantasy VII was. Rather, if the game’s aesthetics elicits prestige, it is partly a result of Sandfall’s decision to use Unreal Engine 5 to create a detailed and realistic world modeled on the Belle Époque. As a result, characters are caked in blood and mud, areas contain minute details that lend themselves towards environmental storytelling, and expressive facial animations heighten the narrative drama. Without a doubt, Unreal Engine is not beholden to specific styles. Both Persona 3 Reload (P-Studio, 2024) and Romancing SaGa 2: Revenge of the Seven (xeen Inc., 2024) are anime style games made with Unreal. But as Jim Malazita argues, Unreal’s capability for photorealism, “…traffics in multiple kinds of white vision and authority.”18 That is to say that Unreal’s capacity for photorealism is part of a larger hegemonic structure of visual culture, including painting, photography, and cinema, one that has historically privileged mechanically produced images as the aesthetic par excellence. Andre Bazin articulated a foundational version of this argument over sixty years ago when he suggested that the objectivity of photography allows it to become, “the most important event in the history of the plastic arts.”19 It seems then that when discussing how games incorporate qualities of cinema, it is not necessarily a matter of whether or how games employ long-takes, shot-reverse-shots, or jump-cuts, but rather how games produce the camera’s mechanical gaze as a means to be “serious.” Clair Obscur thereby emerges as the most important event in the history of the JRPG because even as characters battle strange creatures and traverse surreal environments, the game still draws upon elements of realism.

Part of the mythology surrounding Clair Obscur has been on how the game was made by a small group of amateurs who had turned towards Unreal for its affordability—a recent New York Times article revealed that the development budget was a mere $10-million,20 a fraction of Final Fantasy XVI‘s reportedly $58.3-million cost.21 In the wake of failing to recoup ever soaring developmental investments, the contemporary games industry finds itself crashing and burning, especially as companies are intent on using generative A.I. to cut labor expenditure. At some point in time, something has to give, but the narrative surrounding Clair Obscur demonstrates that it is possible to make successful games on a fraction of the budget. That is to say, a sustainable method to produce widely popular and commercially successful games exists. My point here is not to uphold Clair Obscur as the future of the JRPG, but rather to point out that the history of the genre in the Anglosphere is merely a twisted reflection of how the JRPG actually developed, with dozens of titles remaining unlocalized or inaccessible, leading to this precise scenario surrounding Clair Obscur. The curse of Final Fantasy has been to represent the entire JRPG genre when Japanese developers, both big and small, have long demonstrated a rich diversity in approaches.

I am not naïve enough to believe that the sudden localization of Gunparade March (Alfa System, 2000) or Sakura Wars 3: Paris is Burning? (Sega, 2001) would lead the same person who sneers at Final Fantasy XIII to have a greater appreciation of the JRPG genre and the works which influenced it. One need to only look at the negative reception of titles such as Unlimited SaGa (Square 2002) and Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter (Capcom, 2002) to understand that the question is not about wanting more radical titles. But with recent games such as Angeline Era (Analgesis Productions, 2025) and [DE:] Fanastasis (Mosamosa, 2024), the genre proves that it is far from stagnant and perhaps richer than the more conservative design ethos of Clair Obscur gives it credit for.

If you have read this as being critical of Clair Obscur itself then you have missed the point. The issues I bring up here are neither with the game nor Sandfall themselves, but rather in the community and the discussion surrounding JRPGs—the ways in which discourse functions as an institution to control knowledge.22 For those who came before. The games which have been left behind, snubbed, or forgotten by history.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

360. “Could Final Fantasy XIII Finally Transform the JRPG?” 360, no. 62 (January 2010): 56 – 57.

4Gamer. “‘Persona,’ ‘Catherine,’ ‘Metaphor’ ni jitsu wa kyōtsūten? Hashino Kei-shi × Soejima Shigenori-shi ga kataru, kioku no sekkeiron to wa [G-STAR 2025]” [Do Persona, Catherine, and Metaphor Actually Have Something in Common? Katsura Hashino × Shigenori Soejima Discuss the Design Theory of Memory]. November 15, 2025. https://www.4gamer.net/games/714/G071477/20251114074/

Andiloro, Andrea. “Premiers to Pixels: The Discourse of Cinema Envy in 1990s Videogame Magazines.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 0, no. 0 (2025): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565251404000

Ashcraft, Brian. “Japanese Games ‘Just Suck’ Target Speaks Out.” Kotaku, March 9, 2012. https://kotaku.com/japanese-games-just-suck-target-speaks-out-452565578

Bazin, André. What Is Cinema? Translated by Hugh Gray. Introduction by Dudley Andrew, with essays by Jean Renoir and François Truffaut. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Bogost, Ian. “Q-Up and Candy Crush, say, are more serious works of game than Horses (which seems fine and even innocuous!) or whatever embarrassing anime RPG trash is on Steam or Nintendo eShop.” Bluesky, December 5, 2025. https://bsky.app/profile/ibogost.com/post/3m7ap5o5was2w

Bradley, Kelly. “Saga Frontier 2.” IGN, February 17, 2000. https://www.ign.com/articles/2000/02/18/saga-frontier-2

CNC. “The Story Behind Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, the Breakout Video Game from French Studio Sandfall Interactive.” July 4, 2025. https://www.cnc.fr/web/en/news/the-story-behind-clair-obscur-expedition-33-the-breakout-video-game-from-french-studio-sandfall-interactive_2419300

Consalvo, Mia. Atari to Zelda: Japan’s Video Games in Global Contexts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

Dengeki. “Imēji Epokku ga tasū no JRPG happyō!! Nakama o rosuto suru Saigo no Yakusoku no Monogatari nado” [Imageepoch Announces Several JRPGs, Including The Story of the Last Promise, a Game Where You Can Lose Companions, and More]. Dengeki, November 24, 2010. https://dengekionline.com/elem/000/000/323/323263/

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

GameFan. “GameFan RPG Top Ten.” GameFan, August 2000, 19.

Harper Jay. “The Attempt to Escape From Pain Creates More Pain.” Transgamerthoughts, December 12, 2025. https://transgamerthoughts.com/post/802763182951301120/the-attempt-to-escape-from-pain-creates-more-pain

Lewis, Catherine. “Former Square Enix Exec Says That’s Nothing New as Major Investor Calls Out the Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest Creator for High Development Costs and Lackluster Sales.” Games Radar, December 9, 2025. https://www.gamesradar.com/games/final-fantasy/former-square-enix-exec-says-thats-nothing-new-as-major-investor-calls-out-the-final-fantasy-and-dragon-quest-creator-for-high-development-costs-and-lackluster-sales/

Malazita, James. Enacting Platforms: Feminist Technoscience and the Unreal Engine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2024.

Mills, Brent. “What Does It Mean to Call Television ‘Cinematic’?” In Television Aesthetics and Style, edited by Jason Jacobs and Steven Peacock, 49–65. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Morell, Chris. “Final Fantasy XIII: Your Questions Answered.” PlayStation Blog, February 12, 2010. https://blog.playstation.com/2010/02/12/final-fantasy-xiii-your-questions-answered/comment-page-2/

Small, Zachary. “A Gaming Tour de Force That Is Very, Very French.” New York Times, December 11, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/11/arts/clair-obscur-expedition-33-sandfall.html

Tabuchi, Hiroko. “One on One: Keiji Inafune, Game Designer.” New York Times, September 20, 2010. https://archive.nytimes.com/bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/20/one-on-one-keiji-inafune-game-designer/

Van Allen, Eric. “Clair Obscur Developers Visited Square Enix’s Offices for a ‘Rich Exchange’ of Ideas.” IGN, July 25, 2025. https://www.ign.com/articles/clair-obscur-developers-visited-square-enixs-offices-for-a-rich-exchange-of-ideas

Yin-Poole, Wesley. “Square Enix Admits Final Fantasy XVI and Final Fantasy VII Rebirth Profits ‘Did Not Meet Our Expectations.’” IGN, September 18, 2024. https://www.ign.com/articles/square-enix-admits-final-fantasy-16-and-7-rebirth-profits-did-not-meet-our-expectations

END NOTES

- Kelly Bradley, “Saga Frontier 2,” IGN. February 17, 2000. https://www.ign.com/articles/2000/02/18/saga-frontier-2 ↩︎

- GameFan, “GameFan RPG Top Ten,” GameFan, August 2000, 19. ↩︎

- Chris Morell, “Final Fantasy XIII: Your Questions Answered,” February 12, 2010, PlayStation Blog, https://blog.playstation.com/2010/02/12/final-fantasy-xiii-your-questions-answered/comment-page-2/ ↩︎

- 360, “Could Final Fantasy XIII: finally transform the JRPG?” 360 Issue 62, January 1, 2010, 56. ↩︎

- Mia Consalvo, Atari to Zelda: Japan’s Video Games in Global Contexts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 5. ↩︎

- Wesley Yin-Poole, “Square Enix Admits Final Fantasy 16 and 7 Rebirth Profits ‘Did Not Meet Our Expectations,’ IGN, September 18, 2024, https://www.ign.com/articles/square-enix-admits-final-fantasy-16-and-7-rebirth-profits-did-not-meet-our-expectations ↩︎

- Eric Van Allen, “Clair Obscur Developers Visited Square Enix’s Offices For a ‘Rich Exchange’ of Ideas,” IGN, July 25, 2025. https://www.ign.com/articles/clair-obscur-developers-visited-square-enixs-offices-for-a-rich-exchange-of-ideas ↩︎

- Hiroko Tabuchi, “One on One: Keiji Inafune, Game Designer.” The New York Times. September 20, 2010. https://archive.nytimes.com/bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/20/one-on-one-keiji-inafune-game-designer/ ↩︎

- Brian Ashcraft, “Japanese Games “Just Suck” Target Speaks Out.” Kotaku. March 9, 2012. https://kotaku.com/japanese-games-just-suck-target-speaks-out-452565578 ↩︎

- Dengeki, “Imēji Epokku ga tasū no JRPG happyō!! Nakama o rosuto suru Saigo no Yakusoku no Monogatari nado” (Imageepoch Announces Several JRPGS including The Story of the Last Promise, A Game Where You Can Lose Companions, and More”) Dengeki, November 24, 2010. https://dengekionline.com/elem/000/000/323/323263/ ↩︎

- 4Gamer, “‘Persona’ ‘Catherine’ ‘Metaphor’ ni jitsu wa kyōtsūten? Hashino Kei-shi × Soejima Shigenori-shi ga kataru, kioku no sekkeiron to wa [G-STAR 2025]” (Do Persona, Catherine, and Metaphor Actually Have Something in Common? Katsura Hashino × Shigenori Soejima Discuss the Design Theory of Memory [G-STAR 2025], November 15, 2025, https://www.4gamer.net/games/714/G071477/20251114074/ ↩︎

- Ian Bogost, “Q-Up and Candy Crush, say, are more serious works of game than Horses (which seems fine and even innocuous!) or whatever embarrassing anime RPG trash is on Steam or Nintendo EShop,” Bluesky, December 5, 2025, https://bsky.app/profile/ibogost.com/post/3m7ap5o5was2w ↩︎

- Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 58. ↩︎

- Brent Mills, “What Does It Mean to Call Television ‘Cinematic’?” in Television Aesthetics and Style, ed. Jason Jacobs and Steven Peacock (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 57. ↩︎

- Harper Jay, “The Attempt to Escape From Pain Creates More Pain,” Transgamerthoughts, December 12, 2025, https://transgamerthoughts.com/post/802763182951301120/the-attempt-to-escape-from-pain-creates-more-pain. ↩︎

- Andrea Andiloro, “Premiers to Pixels: The Discourse of Cinema Envy in 1990s Videogame Magazines,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 0, no. 0 (2025): 1–18. DOI: 10.1177/13548565251404000 ↩︎

- CNC, “The Story Behind “Clair Obscur: Expedition 33”, the breakout video game from French studio Sandfall Interactive,” July 4, 2025, CNC https://www.cnc.fr/web/en/news/the-story-behind-clair-obscur-expedition-33-the-breakout-video-game-from-french-studio-sandfall-interactive_2419300 ↩︎

- James Malazita, Enacting Platforms: Feminist Technoscience and the Unreal Engine (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2024), 148. ↩︎

- André Bazin, What Is Cinema?, trans. Hugh Gray, intro. Dudley Andrew, with Jean Renoir and François Truffaut (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 16. ↩︎

- Zachary Small, “A Gaming Tour de Force That Is Very, Very French.” The New York Times. December 11, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/11/arts/clair-obscur-expedition-33-sandfall.html ↩︎

- Catherine Lewis, “Former Square Enix exec says that’s nothing new as major investor calsl out the Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest creator for high development costs and lackluster sales.” Games Radar. December 9, 2025. https://www.gamesradar.com/games/final-fantasy/former-square-enix-exec-says-thats-nothing-new-as-major-investor-calls-out-the-final-fantasy-and-dragon-quest-creator-for-high-development-costs-and-lackluster-sales/ ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith, New York: Pantheon Books, 116. ↩︎